The house we live in is over 90 years old. Sometime in the early 1930s, as a shaken city emerged from the Depression and the earliest electric streetcars were still rolling up and down King Street a block away, she was all scaffolding and workmen whistling.

I like to imagine her back then. New. Bones made of timber and brick and plaster, standing on a little hill. Miles of neighbourhood around her yet to be developed. Just waiting to be filled up with the holiness of ordinary living.

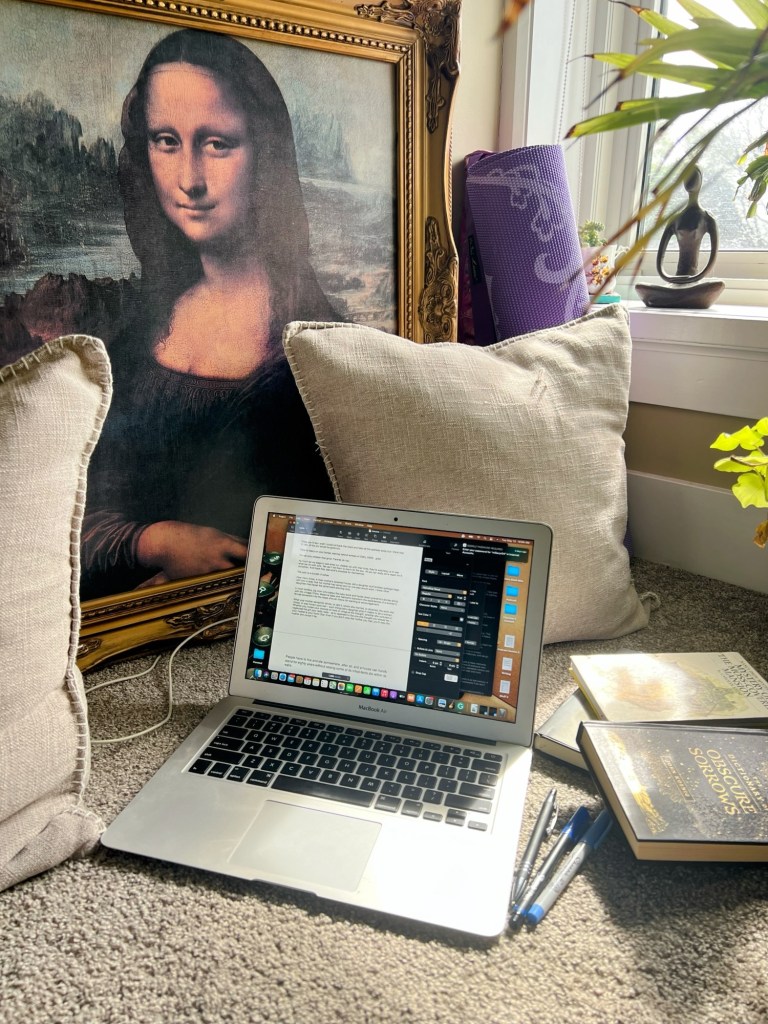

I’ve never owned an old house before. I could count on one hand the number of families who had lived in houses before us in almost all of the other places I’ve ever lived. But this house, even though she’s been modernized now — sleek appliances, polished countertops and hardwood, and the finished attic where I write this — she has carried so many lives. The ghosts of countless beginnings and unravellings live in her walls. Her floors hold footsteps like memory. Every creak is someone’s echo.

Inside her generous spaces, you can still feel the people who came before us, like shadows that move just outside your vision. One day, I’ll do the research to know who once lived here but for now, I imagine. A couple who argued in the kitchen about the bills and then made love hours later under a leaky roof. A widow who grew tomatoes in the backyard and never quite stopped setting the table for two. The little boy who accidentally slipped his dad’s ’72 Impala into gear, scratching the fender when it hit the original garage. The little girl who lined her book shelf with Babysitter’s Club novels, then college textbooks, then nothing at all.

Maybe they left behind a note stuffed under the floorboards. The smell of lavender in the attic. Or names etched into the rafters — like they were saying: “we were here.” And now we’re here. A little part of her history that will vanish long before her four walls do, too.

I’ve always thought of her as a woman because she just feels like one to me. Mother energy. All warmth and wisdom and strength. Always welcoming you back. Her ability to stand, for all of these decades, and take it all in — the grief, the joy, the laughter and tears — the ordinary, endless ache of trying. All the while saying very little. That’s most of the women I know.

She knows what it is to hold things quietly, to carry pain and joy in equal measure, and still to open her arms — or her doors, as the case may be — every morning like it’s the first time. And, like any woman who endures, she’s got her secrets.

She’s seen enough of families to know that you inherit more than eye colour and blood type; you also inherit the silence, repression and survival strategies your ancestors used to endure. She knows the unconscious isn’t just a place buried inside of us. It’s cultural. It’s collective. And it’s carried through the bodies of every generation. The body holds the story.

And she knows that there’s a part of life that only happens in kitchens in the morning before anyone decides who they’ll be today. No sunlight on any face yet. The crumbs from yesterday still underfoot. She could tell them, if they’d listen, that some of us are born twice. The first time for the world. The second time for ourselves. Hang on for that. That’s what she’d say.

She’s seen broken homes that had nothing to do with divorce. Unions that started in fire and ended in ash. Marriages of familiar strangers that softened over time like cotton sheets worn thin by loving. And a few between two people with love beyond measure. She didn’t choose who came, who stayed or who left — but she remembers them all. The joys, the aches, the whispered I do’s, the slammed doors. Because that’s what houses do. They stand still while we come undone.

She never judged the mess because she knows that life is only made up of moments — among them countless ordinary and wonderful joys — tiny pieces of glittering mica in a long stretch of gray cement. These days, it would be wonderful if they came to us unsummoned, but particularly in lives as busy as the ones most of us lead now, she sees that doesn’t happen. She knows we have to teach ourselves to make room for them. To love them. To live in them.

She’s watched children grow. It’s surely one of her favourite things. And after decades of observing, she knows that it isn’t just the little ones who grow — parents do too. Some to the point of knowing that their kids don’t need to see their perfection. They just need to see them happy. They need to see them love themselves — so they know how too.

And she knows beauty, the way an old woman knows pain—not as something delicate or rare, but as something that keeps showing up, even when no one’s looking.

It was in the hum of a record player in 1973, Fleetwood Mac spinning like a prayer in the living room. It was in the crooked crayon drawings taped to the fridge, the ones that said: “I see the world and I want you to see it too”. It was in the arguments that turned into poems, in the letters shoved in drawers, in the lullabies sung to babies who are now grown. She has held symphonies in silence, seen art in the smudge of paint on floorboards, loved language for the way someone whispered “stay” — and someone else did. Beauty, she would say, isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s just what’s left behind when everyone’s gone.

She’s been present for everything — she’s seen first steps and heard the silence after the last breath. Watched as love ripped itself out of chests. She didn’t flinch. She stayed through it all— the quiet keeper of life’s most fragile and important moments. And in her silence, she’s offered something that no living thing could: presence without condition.

Like the best of people, she teaches without speaking. That sometimes the most sacred thing we can do is bear witness. And that what matters most is how open you’ve been — and how well you’ve held the people you were given.

Leave a comment